A “Hard, Ugly Truth”?

So many suffer in this world, and we should care about that. We should obey the command to “love thy neighbor.” But do we really? And is a better world near?

Billionaire venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya, a former part-owner of the National Basketball Association’s Golden State Warriors, shocked listeners to his All-In Podcast last January when he shared his opinion on a pressing human rights issue: “Nobody cares about what’s happening to the Uyghurs.... You bring it up because you really care, and I think it’s nice that you really care, the rest of us don’t care…. Of all the things I care about, yes, it’s below my line.”

The NBA, carefully managing its relations with China, has been wracked with concerns about treatment of the Uyghurs, a largely Muslim minority group in western China. And many listeners expressed concern about Palihapitiya’s statement. National Public Radio, reflecting on the controversy, reported, “Palihapitiya said he cares about many things, including inflation, American health care infrastructure and climate change, but not the genocide China is accused of carrying out against the Muslim Uyghurs” (“Co-owner of NBA’s Warriors slammed after saying ‘nobody cares about the Uyghurs,’” NPR.org, January 17, 2022).

Was Palihapitiya correct when he said, “Nobody cares about what’s happening to the Uyghurs”? Or is he more calloused than the rest of us? To some, it might seem Palihapitiya was bluntly saying that we shouldn’t upset a nation that offers investors vast potential profits, simply because of a faceless mass of people who are effectively no more relevant to most people than the bugs that hit our windshield as we drive on a warm summer night.

Palihapitiya elsewhere tried to temper his comments, saying he was trying to make a point about American hypocrisy and that he did not intend to express any personal lack of empathy for the Uyghurs. Yet, though most would deny it, Palihapitiya’s comment—even taken at face value—described reality far too accurately. Perhaps many more think this way than would ever openly say so on a public forum. As he put it, “I’m just telling you a very hard, ugly truth.”

Out of Sight, Out of Mind?

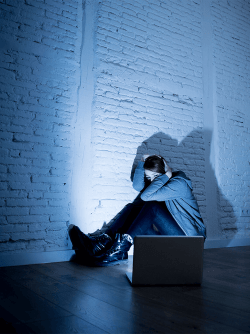

At the same time, there are those who would vociferously disagree and claim that they do care; and maybe they do. This is especially true when caring emotions are stoked by a pleading woman’s voice and sentimental background music, accompanied by a video of starving African or Asian children sitting on parched ground and covered with flies. Such appeals are certainly effective in generating money for charities. Whatever else you think, only the most hardened among us are not touched by such pitiful pleas. But such temporary compassion may not be as much an example of genuine love and concern as we try to convince ourselves. Consider this statement from the Bible about those who claim they love God: “If someone says, ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, how can he love God whom he has not seen?” (1 John 4:20).

Are we deceiving ourselves about the meaning of love when we claim to love a faceless, distant stranger? After all, the stranger has never cut us off in traffic or undermined us at work. Would we still love him if he were closer? However poorly he expressed himself, Palihapitiya might have hit upon a kernel of truth about hypocrisy, and about avoiding the proverbial victim by the wayside (Luke 10:30–32). Can we truly say we love someone far away when we cannot love someone close by? Is sentiment the same as true love?

Are these simply abstract philosophical questions over which we should not burden ourselves? Or is there a lesson they can teach us through self-examination?

Putting on a Face

It is easy to have temporary sentimental feelings, yet at the same time—by our actions—dismiss people as being less human than we are. It is easy to act as though others do not experience hunger, disappointment, depression, or fear as we do, and that the loss of their children does not pain them as would the loss of our own. It is easy to forget that they have hopes and dreams, the desire to love and be loved. Yes, it is easy to dismiss the needs and concerns of faceless, faraway masses as if they were less than us—even if we deny this, even to ourselves.

The 2004 “Christmas Tsunami” in South Asia was a tragedy of monumental proportions, killing more than 230,000 people. Pictures of the destruction, horrendous as they are, cannot begin to reveal the magnitude of human suffering that occurred when for ten minutes a 900-mile fault beneath the Indian Ocean slipped and shook millions of square miles of land and sea.

We can understand that the thousands of European, North American, and Australian tourists in the coastal province of Phuket, Thailand and elsewhere in the affected areas did not see the indigenous victims as nameless and faceless. Nor did a dear friend of mine in Canada whose family narrowly survived the waves that struck Sri Lanka. This friend put a face on them for me.

Around the World

Two-and-a-half years ago, just as COVID-19 was leading to lockdowns almost everywhere, I had the wonderful opportunity to travel literally around the world on an extended trip for Tomorrow’s World. My trip began in Canada, where for more than 13 years I had lived in a multicultural neighborhood so diverse that every one of us was a minority. I was there to record four Canadian version Tomorrow’s World telecasts. After that, I flew to the Philippines and then to Thailand for ministerial conferences and to visit a school in Mae Sot, Thailand, where our foundation teaches English. Then it was on to South Africa by way of Singapore.

South Africa was a whirlwind. I spent the Sabbath with our Johannesburg and Pretoria congregations and then flew to Cape Town for a Tomorrow’s World Presentation on Sunday. From there, it was off to Port Elizabeth to meet with Church members before a flight to meet with our office manager and his wife, where the three of us drove to Lesotho, a country within a country. I also visited our South African office and met the staff there before returning to Johannesburg to fly home.

Every place I traveled, I saw faces and people that I will not easily forget—and will not write off. It is not that this was a revelation to me, as I have traveled more than most Americans, having lived in Canada and England and having visited China, India, Israel, Mexico, France, and Germany, as well as many other places. Yes, people dress differently and have different customs, but all are just as we are—human beings made in the image of God with the same godly potential.

Tomorrow’s World is here to explain God’s plan of salvation—His biblical plan that is not taught in mainstream Christianity or in any other religion. The Bible nowhere teaches that we are here to live with as much pleasure as we can cram into our fleeting years and then go to a celestial retirement in the sky, or to an ever-burning hellfire to be tortured forever! So, why is it that the plain teaching of Scripture is almost never taught?

King David asked, “What is man that You are mindful of him?” The second chapter of Hebrews answers that question. Read it for yourself. Also check out Romans 8:14–23, Luke 19:11–19, and 2 Corinthians 6:18. And, for a full explanation of God’s plan for you, order our free resources What Is the Meaning of Life? and The Holy Days: God’s Master Plan. What God has in mind for you is far greater than you can imagine. He has not written off the Uyghurs or any other people on planet Earth—nor should we!

You and I will not solve all of mankind’s problems now, but there is coming a time in the future—a time we call tomorrow’s world—when the One who created mankind with different talents and abilities will return to straighten out the mess we see around us, whether near or far. While we as human beings may forget those far off, He will not. He has a plan for everyone. Keep reading this magazine to learn more about that plan and the soon-coming kingdom of God!