The Chunnel: Icon of National Cooperation

Thirty years ago, on July 29, 1987, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and French President François Mitterrand signed an historic agreement to build a train tunnel under the English Channel. Its purpose was to allow faster and more efficient travel between France and England. This engineering marvel is called the Eurotunnel, Channel Tunnel, or affectionately, “the Chunnel.” This connection between Britain and France has benefited both sides, but what does this accomplishment portend for the future? Is it possible that the Eurotunnel could serve as a symbol of the type of cooperation all nations will one day exhibit?

A More Cordial Relationship

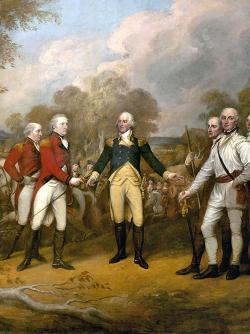

It is no great secret that the British and French relationship over the centuries has been afflicted with war and resentment. But, after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and the end of France’s domination of Europe, there was a marked improvement in how the two nations got on with each other. Nearly a century later, on April 8, 1904, the Entente Cordiale was signed. This Anglo-French agreement resolved long-standing antagonisms by settling a number of difficult and controversial issues.

The Entente Cordiale paved the way for cooperation between England and France in the decade leading up to the Second World War and beyond. It lessened the isolation both France and England had assumed, the former by obligation and the latter willingly. War had turned to peace, and peace led to the possibility of cooperation. With friendship fanned into a healthy flame, the path was paved for the accomplishment of something truly magnificent, if only the Franco-British relationship could be freed from the constricting grip of national security fears, cultural differences, and funding woes.

A Bold and Ambitious Dream

The dream of overcoming the natural water barrier separating Britain from the European continent dates back to 1785, when a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, and an American, John Jeffries, successfully navigated the skies above the English Channel via hot air balloon. However, it was “Napoleon’s engineer, Albert Mathieu, [who] planned the first tunnel under the English Channel in 1802, envisioning an underground passage with ventilation chimneys that would stretch above the waves” (“English Channel tunnel opens,” History.com). His was a bold and ambitious plan, yet too early for practical development. Another Frenchman, Thomé de Gamond, is considered the real “father” of the tunnel between France and England. Gamond proposed prefabricated tube tunnels. They would rest on the channel floor, rather than be bored through the hard earth beneath.

It was the invention of the tunnel boring machine (TBM) in 1875 that brought the dream closer to reality. The early TBMs were capable of boring at a speed of five feet per hour. By comparison, the eleven 800-foot-long TBMs used to eventually complete the Eurotunnel could rip through the hardest rock at 15 feet per hour, a 200-percent increase in tunnelling efficiency!

Drilling began in 1881 off the coast of England at Dover, and in Calais on the French coast. National security fears halted the drilling, however, after both sides reached only the 5,000-foot mark. In 1974, TBMs resumed biting their way through the chalk marl sandwiched between solid bedrock and with the intense pressure of the water-filled Channel bearing down from above. Progress was again halted, but this time it was due primarily to a failure to secure funding by the British government.

The Dream Becomes Reality

Then, in 1987, Margaret Thatcher and François Mitterrand signed the historic agreement to build the tunnel. Both sides agreed that it would be wholly funded by private investors. The final design was for three tunnels. Two 25-foot diameter tunnels would take passengers and cargo by train, each in one direction. A smaller bi-directional service tunnel would be used for maintenance and emergencies. A group of British and French engineering construction companies built the 31-mile tunnel (23 miles of which is underwater, making it the longest underwater train tunnel in the world) over a period of seven years, using 7,000 workers 300 feet beneath the English Channel. The total cost of the project was £12 billion in today’s currency, surpassing the original budget by more than fifty percent. The tunnel opened for service on May 6, 1994. With train speeds of up to 100 mph, a trip from London to Paris is possible in only three hours.

A Symbol of Hope, Tried by Fire

The “Chunnel,” named one of the “Seven Wonders of the World” in 1996, ironically suffered its most notable fire on November 18 of the same year. This symbol of national cooperation and a truly great British and French collective achievement was put at great risk—just as the spirit of the Entente Cordiale was also tested by a humanitarian “fire” in the form of the migrant crisis of 2016.

The tunnel was seen as the conduit to a better life for those fleeing from war-torn parts of Africa and the Middle East, and the entrance of the Eurotunnel in Calais became the pinch point as the crisis spread across Europe.

The political landscape was “terra-formed” by the Brexit referendum vote held on June 23, 2016. To the great dismay of many, 51.9 percent of the British voting public chose to leave, rather than to remain in the European Union (EU). Even those who voted to leave were feeling what was at the time being called “Regrexit.” This regret could be likened to “buyer’s remorse”—when, after purchasing something greatly sought after, the reality of the true cost becomes clear—and many individuals across the United Kingdom were left scratching their heads, wondering what had transpired, and many others wanting to turn back the hands of time.

That would not be the case, however, as the “divorce papers” were activated by Prime Minister Theresa May on March 29, 2017, in the form of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. So began a two-year timetable of negotiations about the future relationship between a separate Britain and the European Union. Current feelings between Europe and the United Kingdom have changed dramatically since the days of the dream of connecting Britain to the continent!

National Cooperation Is Coming!

The cooperation exhibited between once-warring nations, Britain and France, and the engineering wonder they produced is an example of the kind of cooperative effort that will be made possible after the return of Jesus Christ. Humanity has not known peace (Isaiah 59:8), but in the future, “nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isaiah 2:4).

While it is true that the nations have not known the way of peace, there have been glimmers of cooperative peace and shared accomplishment. The Eurotunnel is just one such example. After the return of Jesus Christ to this earth, the possibility for more shared achievements—by nations that will then truly be at peace with each other—will become a joyous reality for all.