Liberty’s Progress— The American Revolution from a British Perspective

The war that divided the United States from British rule had a richer set of causes and effects than many people understand—and was used by God to fulfill His will for both nations.

Some two miles from my home in Somerset, England, stands Dillington House, the former country estate of Lord Frederick North, Prime Minister of Great Britain between 1770 and 1782. His Tory government served under George III, the infamous Hanoverian King, who in later life suffered from a severe and incapacitating mental illness (now thought to be caused by the genetic blood disease porphyria).

King George and Lord North’s lasting claim to fame is that “on their watch” they “lost” the 13 American colonies in the Revolutionary War of 1775–1781, or the American War of Independence, as it has come to be known.

The separation of the American colonies from Britain proved to be one of the great turning points in history, as America grew from humble beginnings to become the dominant world superpower, rooted in the ideals of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” expressed in the famous Declaration of Independence. Over the last century, the U.S. has exerted influence over the entire world, dominating language, culture, business and commerce, and exercising overwhelming military prowess.

How did this happen and why? What lessons can be learned from the birth of the most powerful nation the world has ever known, especially from the perspective of the British Empire—the greatest empire the world has ever known?

Fighting the French

The story of how this all came about begins at a time when Britain saw that the key to her future prosperity and influence lay in creating a worldwide trading empire. Her greatest challenges to this were from her colonial competitors in Europe, especially the French, who in 1756 began an all-out attack on the British quest for colonial supremacy, beginning the Seven Years’ War.

In North America, France—which controlled the central part of the continent—sided with the Abenaki Confederacy of Native Americans against British interests: its thirteen colonies in the east, and those to the north in Canada. The colonists showed distinct loyalty to Britain by providing tens of thousands of troops to engage in the struggle. Britain and the colonists decisively won that war, which concluded with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, out of which Britain gained control of Canada from the French and Florida from the Spanish.

But all was not well in the relationship between the American Colonies and Britain. Above all, the colonists wanted to be treated with greater respect and consultation, and not just be dictated to by the King of England and Parliament back in London. What developed was an escalating clash of perspectives and priorities, with the colonists increasingly feeling that their interests were not being adequately represented.

A Royal Proclamation of 1763 placed a limit on the westward expansion of the American colonies. The aim was to divert colonial expansion towards the north (Nova Scotia) and towards the south (Florida). This imposition was unpopular with a vocal minority and contributed to a growing sense of conflict between the colonists and their British masters.

Then, cash-strapped Britain, struggling after the Seven Years’ War to finance its increasingly global empire, thought it would be appropriate for the expanding colonies to contribute toward their defence against Indian uprisings and the possibility of future French incursions. The colonists bitterly complained, not directly about the taxes, but on the issue of whether Parliament could levy a tax on the American colonists without their approval. After all, America had no seats and no say in Parliament. The colonists were not exactly being rebellious; they were behaving like all “good” Englishmen back home, who had insisted on “no taxation without representation”! This slogan was not truly “a rejection of Britishness, but rather an emphatic assertion of Britishness” (Ferguson, Niall. Empire—How Britain Made the Modern World, Penguin, 2003. p. 93).

The stage was steadily being set for a mighty showdown. In 1765, Parliament introduced the Stamp Act, which levied a stamp duty on every document in the British colonies of North America. Perhaps by design, this tax fell most heavily on those radicals producing newspapers that attacked these very taxes; protests ensued and resulted in refusal by the colonies to comply.

When a change of government in London repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, there was widespread jubilation in the colonies. But London also emphatically declared that Parliament had the absolute power to make binding on any of its colonies whatever laws and changes it saw fit—even though the colonists were not represented in Parliament. There were cries of horror in the colonies at what was seen as the denial of Anglo-Saxon liberties hard won over many generations.

Then, in 1767, heavy import duties were placed on a range of products (including tea) coming into America. The aim was simply to raise money to pay for the costs of administering the colonies. But the reaction was more horror and alienation—which, by 1769, bordered on insurrection and treason by North American assemblies.

The Empire Strikes Back

And now, in 1770, enters Lord North. One of his first acts was to remove all the recent taxes, except the one on tea. Though this was welcome to the colonists, they were boycotting goods from Britain whenever it suited them and generally refusing to cooperate with London. Lord North’s government went ahead with its plans anyway and imposed the import of large amounts of surplus tea held by the East India Company into America, but with a much lower tax rate than that imposed upon Britain. At a stroke, this was one part of the British Empire helping another part of the empire on the opposite side of the world.

But this was not how many Americans saw things. Paradoxically, tea had never been cheaper. But the East India company was given a monopoly on importing tea into America, and the ones who suffered most from this were the wealthy Boston smugglers. It was they who organized the famed Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, when people disguised as Mohawk Indians dumped 342 boxes of tea, as yet unloaded from ships, into the Boston harbor. This relatively trivial event of national resistance proved to be an incendiary moment.

Lord North’s government responded harshly with a series of Acts in 1774, collectively known by Americans as The Intolerable Acts. Boston Harbor would be closed down until adequate compensation for the lost tea was forthcoming from the townspeople. The charter of the Massachusetts colony was revoked, and the governor of Massachusetts received the authority to billet any of his troops in the homes of any settlers he chose.

In addition, Parliament agreed to preserve the French system of civil law and allow 70,000 French-speaking Catholics in Canada to practice their faith without penalties, and their church to be supported by tithes. To the majority of Protestant Americans, these developments reinforced their worst fears about rule from London. For them it heralded trial without juries, the end of habeas corpus, and a government without an elected assembly (Shama, Simon. A History of Britain, Vol. 2 The British Wars, 1603-1776. BBC, 2001. pp. 464–470; Lee, Christopher. This Sceptered Isle—Empire. BBC, 2005. pp. 173–176). America was now already far beyond the point of accepting even the principle of being taxed by Parliament in London.

The reaction in London to what was happening across the sea was bitterly divided. Merchants and traders feared for their livelihoods if war were to break out. But the mood of the king and Parliament was all for teaching the “rebellious” Americans a lesson they would never forget. So, the die was cast and King George III declared that the Americans were in a state of “open and avowed rebellion,” generating conflict “for the purpose of establishing an independent empire.” War was all but certain.

As far as the Americans were concerned, if a war was to be fought, it was with an empire that had corrupted itself and no longer represented liberty, but now embodied a perversion of the principles upon which it had been founded (Shama, p. 477).

The War Itself

The British Parliament hoped that their superior armed forces, allied with those Americans who remained loyal to the Crown (called “loyalists”), would quickly deliver a short, sharp shock to aspirations of independence, bringing the colonies rapidly to heel and back into submission to British rule.

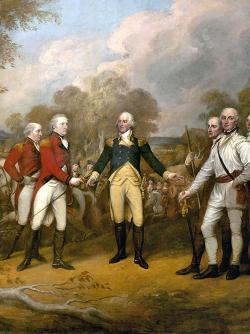

But things did not work out as the British intended. An epic struggle set in, pitting the superbly trained and equipped British naval and land forces against a ragtag, ill-disciplined, poorly trained, poorly equipped, and only recently formed Continental Army. George Washington was the distinguished and experienced general charged with the uphill task of molding the army into a credible fighting force that could eventually carry the day.

The British were somewhat hamstrung, partly by a reluctance to fully engage in what many characterized as a civil war between essentially the same people, and partly by the need to commit their forces elsewhere in the world to other struggles (with the French) already in progress. The constant hope was that the inferior American forces would see the hopelessness of their cause and simply give up.

Then France, Spain, and the Netherlands opportunistically joined in the conflict on the side of the Americans in hopes of regaining territories lost in the Seven Years’ War. The war culminated in October 1781 with an infamous defeat for the British at Yorktown in the south, with the French navy blockading escape by sea, and the now superior Franco-American forces covering the land. General Cornwallis had no choice but to accept defeat on behalf of Britain, and hostilities were rapidly concluded. Two years later, a peace treaty was signed, in which the British government acknowledged American independence (James, Lawrence. Warrior Race—A History of the British at War. Abacus, 2001. p. 242). One of the first acts by Washington after the victory was completed was to disband the Continental Army and return to his beloved “Mount Vernon” plantation in Virginia to plan the next steps for the new nation.

The Blossoming of America

The consequences of the war were profound for America in numerous ways. It now had the freedom it craved to develop as it wished without the colonial subservience demanded by the king and Parliament. America became “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” eventually creating a uniquely crafted Constitution to protect the Declaration’s principles of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Many came to think that America held a “manifest destiny” to spread across the continent—intended by God to be exceptional and to become that shining “city upon a hill” representing a better way of life to the world.

The meteoric rise of America could continue and quicken, built on a rising tide of immigrants buying into American identity, freedoms, and prospects. The vast potential of America’s natural resources could be fully developed: in coal, oil and gas, in steel, in timber, and in agriculture. Life and liberty were plentiful for all, and happiness could now be pursued in earnest (though it would take a bloody civil war and many other societal changes to see such opportunities extended to all who lived within America’s borders). U.S. trade with the rest of the world could proceed unfettered and unhindered.

With the British navy no longer protecting U.S. interests, an American navy soon began to take shape to do the job itself, beginning with the North African Barbary coast. This was a navy destined to one day totally eclipse the might of the British Navy, and to eventually sail unopposed astride all the world’s oceans—and under them as well. The U.S. Air Force would one day rule the skies, and America’s once ragtag military would rise to be second to none.

Britain Also Blossoms

What had seemed like a mortal blow to the British Empire failed to materialize. Indeed, the loss of America seemed only to unleash even greater amounts of energy to expand and progress elsewhere. Successive governments mulled over the catastrophic events and slowly reached the conclusion that “it was imprudent and impractical to deprive Britons of legal and political rights once they left home to settle overseas” (James, p. 243).

Fifty or so years later, the 1839 Durham Report on British North America concluded that “Those who govern the white colonies should be accountable to representative assemblies of the colonists, and not simply to the agents of a distant royal authority.” This is precisely what the earlier generation of British politicians had denied to the American colonies. So the balance of power decisively shifted towards the colonists’ elected representatives, with governors taking on a more decorative role, along with that of the monarch. The result was far reaching: the practice of empire could be reconciled with the principle of liberty, without the need for wars of independence.

This vital lesson was well learned. Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand all became self-governing. India followed. And self-government anticipated eventual independence. The British Empire thus came to have a kind of built-in obsolescence—the end result of respect for the principles of freedom and liberty. The British Commonwealth is a compelling testimony of where respect for liberty can lead: to a group of nations voluntarily sharing similar values of governance and based on mutual respect and liberty. Truly, “the War of Independence had dictated the future form and, for that matter, the eventual fate of the British Empire” (James, p. 243).

True Freedom, Liberty and Happiness

One of the great human drives is the yearning for freedom and liberty—the ability to live in peace and to get on with our lives in freedom within reasonable and agreeable laws. But no human efforts to produce freedom, liberty and happiness can possibly be totally successful—life and human nature is simply imperfect and guided by selfishness.

All this points to an overarching question of ultimate importance. Is there a definitive source of happiness, freedom and liberty? One that applies to everyone, regardless of race or nationality? Is there a universal pathway to achieve these ideals?

The answer is yes! It is found in the pages of the Bible, the written expression of God’s will and purpose. Belief in God and following His ways leads to ultimate happiness, peace, freedom and liberty. “For you, brethren, have been called to liberty; only do not use liberty as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love serve one another” (Galatians 5:13).

True liberty and freedom is—at its core—an inner quality that flows from an intimate relationship with God and with the Holy Scriptures, which define what liberty and freedom mean in practice. Keep reading Tomorrow’s World magazine to find out how you can have this true liberty yourself and how it will one day be extended to the whole world.An Ancient Promise Came to Pass

Strangely enough, many a Briton also saw his own country and parliament as a model of liberty and freedom, and their progress in the world as “exceptional.” Indeed, both America and Britain saw themselves as chosen by a higher power to have a powerful impact on the world—and this they certainly did, for good or ill.

Whatever your perspective about this, British and American rule has created a largely free world based on democracy, freedom, and the rule of law. For any who might disagree, one only has to ask what the world would be like ruled by a thousand-year Nazi Reich or a communist collective regime—totalitarian government in dictatorial hands. One shudders to think.

Did Britain and America become great because of the excellence of their constitutional arrangements? Or because the people are intrinsically better than others? No! There is a surprising biblical reason for the ascendency of Britain and America.

When the dying patriarch Jacob (Israel) dispensed God’s blessings on his children, he especially selected two of his grandchildren, the sons of Joseph. Manasseh, the firstborn, would become a great nation, but his younger brother, Ephraim, would be even greater, and would become a multitude of nations (Genesis 48:1–22). This was a prophecy for “the last days” (Genesis 49:1) and provides compelling reasons for associating Manasseh with the United States of America, and Ephraim with Great Britain and her national family of blood relatives.

Together, these sons of Joseph were promised remarkable blessings over and above the other brothers (Genesis 49:22–26). This correlation of identities goes a long way towards solving some basic questions that arise from history and the sense of identity, purpose and “specialness” possessed by the American and British people. And this knowledge provides a greater depth to understanding history—and God’s future plans—than most people today even imagine. Please write for our enlightening booklet The United States and Great Britain in Prophecy to find out more.