The National Dream

One of the most intriguing and outstanding achievements in Canadian history occurred between 1871 and 1885, within two decades of Canada's confederation in 1867: the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) across the continent uniting eastern Canada with its newest province, British Columbia, on the Pacific coast. Today we take this railway for granted, but at the time it proved the most vigourous, acclaimed and possibly foolhardy venture possible. The late Canadian author, Pierre Burton, wrote possibly the most extensive account of this achievement in his two volume set, The Canadian Dream and The Last Spike (McClelland and Stewart Ltd., Toronto, 1970).

A Clear Vision

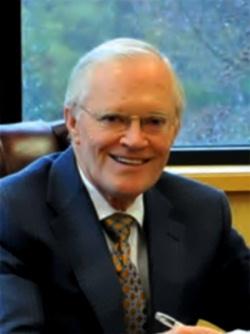

Sir John A. Macdonald—Canada's Conservative leader, "Father of Confederation," and first Prime Minister—had a clear vision of what he perceived Canada should become. It was a national dream that expanded Canada from the Atlantic to the Pacific. At Confederation, Canada was comprised of the four provinces of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, adding Manitoba and Prince Edward Island shortly thereafter (1870). The rest of continental Canada included the vast stretches of the prairies as well as the northern and Arctic territories—a vast wilderness sparsely populated mainly by Native and Metis peoples. The colony of British Columbia was established on the west coast.

Macdonald and others perceived a danger of American incursion into these regions and sought to block it by inviting British Columbia into Canada and settling the prairies with immigrants from eastern Canada and Europe. To lure British Columbia into Confederation, the government at first promised a wagon road joining the two regions, which quickly turned into a promise to build a railroad to unite the west with the east and settle the prairies. Even before construction began, opposition arose in government and in the public. Liberal opposition leader, Alexander MacKenzie, in 1871 referred to it as "an act of insane recklessness" (The National Dream, p. 6).

The Americans had already built their counterpart continental railroad from St. Louis to California in 1869, joined with pre-existing connecting lines in the east. The Canadian Pacific Railway, destined to become the longest railroad in the world until the Trans-Siberian line was built in the Soviet Union in 1925, proved a most difficult endeavour.

Canada, a new nation with a tenth of the population of the United States, had a much smaller industrial and financial base to work with and an economy primarily focused on natural resources. The environment created no end of challenges and deterrents as well. The massive Canadian Shield of northern and western Ontario and part of Manitoba—a massive region of rock—slowed the progress and inflated the cost of construction. The Shield has been described as a near impenetrable mass of rock, lakes, and boggy muskeg—as well as mosquitoes. The severity of the Canadian winter made work extremely difficult, often leading to the necessity of altering and rerouting the line. Serious accidents and mishaps, often caused by bad judgment on the part of construction engineers and management, caused much loss of life and equipment before ever leaving the Shield (ibid. p. 283ff).

The Difficult Path

The prairie region, cut off from the rest of the nation, had its share of difficulties, although the work proceeded more rapidly. Supplies, including rails and lumber for ties, trestles and bridges, had to be moved from Winnipeg to the railhead hundreds of kilometres to the west. Farther to the west the multiple walls of the Rockies and mountain cordilleras created massive barriers to progress, especially in the line started from New Westminster (Vancouver) eastward in the treacherous Fraser Valley. Hundreds, even thousands of lives were lost to accidents, especially through careless handling of explosives—particularly nitroglycerine.

Macdonald's government fell into scandal by 1873 as a result of graft, patronage and corruption concerning the railroad. Contracts awarded to friends and relatives rarely served to promote sound construction. Shady deals and cheap building materials shuffled profits into personal wealth. Macdonald and his government fell into disrepute and were forced out in 1873, replaced by a Mackenzie Liberal government.

Regrettably for the CPR and Canada, MacKenzie's term in office, 1874–1878, proved as corrupt as Macdonald's and even less efficient in regard to the railway. His government collapsed after a literal brawl in Parliament with the Conservatives, who, under Macdonald, again took up the challenge of completing the rail line west. The bickering and debate over the whole notion of the railroad continued unabated, costs escalated by millions, and the deaths of thousands of workmen continued.

But victory followed as kilometre after kilometre of track was painstakingly laid across the wilderness, bridges and tunnels were built, and towns were established. Donald A. Smith, the oldest director of the CPR, drove the final spike uniting the eastern and western lines of the CPR in the wilderness at Craigellachie, British Columbia, east of Shuswap Lake on November 7, 1885.

The national dream and vision for Canada tenaciously held by one man and his followers finally succeeded in spite of nearly insurmountable hardships, scandals, costs, and the collapse of a government. It gave Canada the assurance of a bright future, expanding from the Atlantic to the Pacific, uniting and populating the land with settlers, farms and cities for industries. It opened the way for Canada to become a successful, modern nation.

A Vision of the Future

The building of the CPR was the result of a great vision—one that helped Canada on its way to fulfilling its role in God's design for the world. But in the course of seeing the vision fulfilled, lives were lost, some were treated unfairly and some enriched themselves unjustly. Sadly, this is the current state of the world. Even the most visionary human leader cannot implement a perfect world.

Yet vision is a critical element for getting things done and motivating human beings to strive and achieve what some may consider impossible. It fulfills a very human need: "Where there is no vision, the people perish" (Proverbs 29:18 KJV). Leadership that promotes a big and positive vision of a better world creates hope and energy. Nowhere can one find a more positive vision of a better world than in the prophecies God has written and preserved in the Bible. Here we find a vision of a world indescribably peaceful, productive and happy, with all things achieved without corruption, but through compliance to a perfect set of laws—God's own laws. That vision will be seen to completion by the incorruptible Son of God, Jesus Christ! And unlike Macdonald's vision for Canada, which could only stretch from coast to coast, the Scriptures tell us that the vision of Christ will be boundless: "Of the increase of His government and peace there will be no end" (Isaiah 9:7).

The announcement of this vision is the mission of Tomorrow's World!