Marijuana: What They Aren’t Telling You

Is marijuana as harmless as advocates claim? Could society benefit from legalizing it? Is there a larger picture to consider?

Introduction

Up until only a few years ago, police and drug enforcement officials expended huge efforts to control or eliminate the trafficking and consumption of a plant-based drug we know as marijuana, or cannabis (Cannabis sativa). Despite their efforts in most of the previous century, the drug has remained popular and now sees consumption patterns increasing dramatically in North America and Europe.

Few events have such polarizing power as a debate over cannabis use. After all, many say, cannabis has been with mankind throughout most of recorded history, so what is the problem? Marijuana comes from the Indian hemp plant, which has been cultivated through the ages. Hemp was used in ancient China for making paper and also utilized extensively for the production of rope. It was used so widely for rope and cord manufacturing that hemp plants were a part of most farmsteads in North America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, from ancient times other properties of this plant led to a very different application. Herodotus, in 420 BC, reported that Scythians were making recreational use of cannabis, and thereafter we see hemp mentioned also for its hallucinogenic properties.

Today, the manufacture of hemp rope is still an industry in many parts of the world, but it is the hallucinogenic properties of the female hemp plant that have become the primary focus of attention in recent times.

The leaves, stems and flower buds are harvested, dried and processed into a mixture sold under the common name “marijuana.” The resin of the plant material can be extracted and pressed into balls or bars and sold under the name hashish or hash. While there are almost 400 known chemicals in this plant matter, the chemical that causes the hallucinogenic reaction is known as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The mind-altering effects wrought by THC are the reason marijuana is classified as a drug.

Efforts to legalize the use of marijuana—for both “medicinal” and recreational purposes—continue to grow and find success in the halls of state and national governments.

Is this drug as harmless as its advocates claim? What harm, if any, can accrue from the use of marijuana? Does it have any positive properties that truly offset its negative effects? And is there a larger picture that many fail to see through all the smoke?

There is a great deal of debate on this subject, and individuals are passionate on both sides of the issue. Yet the answers are plain to see when we gather all the facts and review them with an open mind. In this work, we will present those facts to you so that you can judge the matter for yourself.

Chapter 1

If It’s Legal, Isn’t It Safe?

Over the past few years, a social revolution has assailed the Western world, bringing changes that would make our present environment nearly unrecognizable to those who lived only two or three generations ago. Whether altered roles for men and women, national and international security issues, communication via social media, evolving gender definitions, or even how right and wrong are determined—so much has changed.

In the 1960s, the first rumblings of this revolution shook the Western world, as a young generation rejected centuries-old moral values, embraced the concept of free love, and turned increasingly to hallucinogenic drugs for entertainment and escapism. The “hippie” movement of this era popularized cannabis. Since that time, marijuana use has grown rapidly in North America, despite its classification as an illegal drug. Both organized crime and local growers saw lucrative opportunities to sell the drug to a growing market.

Mounting pressure from advocacy groups and media has gradually led to a greater public—and hence political—movement to decriminalize or legalize marijuana. Currently, legislatures in multiple states in the U.S. have approved complete legalization, while others have varying degrees of decriminalization along with tolerance for “medical” marijuana. Canada has approved legislation that would legalize cannabis nationwide. Obviously, governments view legalization as a popular measure—good for votes in subsequent elections.

There seem to be two major rationales driving decriminalization or legalization efforts. The first is a growing social belief that marijuana is a benign substance and bodes no ill for the user’s health or society’s well-being. The second is a sense that law enforcement continues to expend vast resources on marijuana prohibition to little avail, while the drug’s illegal status allows organized crime to benefit from trading it. Hence, many reason that if marijuana were legal, public resources could be deployed elsewhere, while drug profits would benefit the economy and not criminals.

Many people now agree with these two positions. What could possibly be wrong with legalizing a harmless substance and denying criminals a marketplace? Yet there are voices of opposition. Interestingly enough, the loudest objections to marijuana legalization come not from “ultraconservatives” or religious movements, but from a host of medical researchers. The pro-marijuana lobby heaps scorn on these voices but offers little peer-reviewed research to counter the findings of some of the most respected medical institutions on earth. So, what major concerns has modern medical research identified?

Loss of Motivation

The use of marijuana as a hallucinogen is not new. For centuries, the lower classes of the Indian subcontinent used it heavily. There are extensive historical references to such users living in poor conditions in towns, cities, and rural areas. These people were normally considered unmotivated and were generally marginalized.

Interestingly, in 2013 Psychology Today reported a study published by scientists at Imperial College London and King’s College London that strongly linked significant marijuana usage to lower dopamine levels in the brain. Decreased dopamine impacts neurochemical levels in the brain and reduces motivation, making one prone to “amotivational syndrome.”1 This explains the ill-repute of ancient India’s marijuana smokers. Numerous clinical observations have supported this effect of cannabis in regular users.

This is alarming because of the scale of marijuana use. The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) reports that 22 percent of youth and 26 percent of young adults admitted to using marijuana in 2013, which is two and a half times the number of those over 25 who admitted to using the drug, according to Statistics Canada’s Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drug Survey.2 These numbers are almost certainly lower than the actual usage levels.

In the United States, the National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health 2015 estimated that the country had over 22 million users per month, with a widening gender gap showing more male users than female.3

What Happens When Marijuana Is Used?

When one uses marijuana, THC and a host of other chemicals pass into the bloodstream, with some of the active ingredients making their way to the brain. The effects occur very soon after inhaling, or 30 minutes to an hour after ingestion with food, due to a delay in passing the THC through the digestive system into the blood. In the majority of cases, the result seems pleasant to the user, but increasingly, high-potency marijuana can create an unpleasant experience. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reports:

People who have taken large doses of marijuana may experience an acute psychosis, which includes hallucinations, delusions, and a loss of the sense of personal identity. These unpleasant but temporary reactions are distinct from longer-lasting psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, that may be associated with the use of marijuana in vulnerable individuals.4

Now, at a time of increasing legalization, the frequency of negative side effects is rising, prompting physicians to sound an alarm—one that the political class is apparently ignoring.

The Partnership for a Drug Free Canada has for years presented reputable, peer-reviewed scientific studies showing the dangers and the social and economic costs of marijuana use. Yet, despite health experts’ endorsement of these studies, social pressure is driving the political agenda.

Who is right? Are concerns about cannabis unfounded? Surely, many will assume, if cannabis use is so widespread, it must not be very harmful to society. For example, some will point out that according to the CCSA, Canadian youth have the highest rate of marijuana use of any country in the developed world, yet without apparent detriment. However, looking a little deeper makes the scientists’ warnings appear more ominous.

Addiction

The American Psychiatric Association publication Psychiatric News reported on a study appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The report concluded that “marijuana use is linked to multiple adverse effects—particularly in youth.”5 Lead researcher Dr. Nora Volkow stressed “that long-term marijuana use can lead to addiction…. The regular use of marijuana during adolescence is of particular concern, since use by this age group is associated with an increased likelihood of deleterious consequences.” The authors articulated that in 77 studies and literature reviews, negative health consequences were associated with marijuana usage.

The Globe and Mail reported on April 12, 2017 that the Canadian Medical Association, the Canadian Psychiatric Association, and the Canadian Paediatric Society had been expressing their concerns to the Canadian government, with seemingly little impact.6 These organizations are especially concerned about users under the age of 25, for up until that time the brain is still developing. Professor Christina Grant of McMaster University states, “We know that 1 in 7 teenagers who start using cannabis will develop cannabis-use disorder”—a condition that destructively impacts the teenager’s school, work, and family relationships.

This damaging condition Dr. Grant calls “cannabis-use disorder” can lead to an addiction in which the individual user finds it frequently interfering with aspects of day-to-day life. The scale of addiction is hard to determine, but studies suggest that about 17 percent of those who start using the drug in their teens will become dependent.7

Brain Impairment and Mental Health

The same paper presents evidence showing a strong link to psychosis development in cannabis users with a family history of mental illness, even indicating that no researched “safe limit” for marijuana usage exists. Dr. Grant continues, stressing that research shows that teens who smoke pot frequently suffer long-lasting damage to maturing brains, manifesting symptoms such as reduction in memory capacity, attention span, and higher-level decision-making abilities. She also adds that MRI studies have shown “thinning” of the developing brain’s cortex, a region critical for thinking, planning, and organizing.

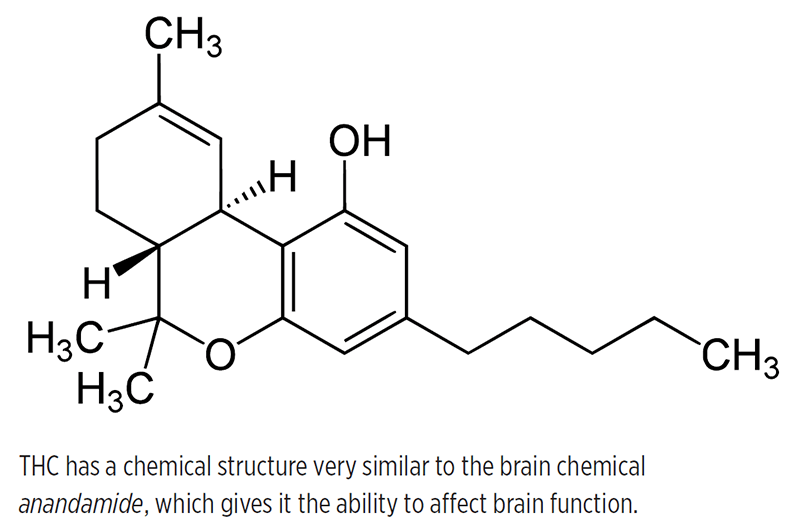

The molecular shape of THC is similar to the brain chemical anandamide to the point where the brain accepts the shape of the THC molecule in place of anandamide, resulting in an alteration in normal brain function. Anandamide (a type of endogenous cannabinoid) functions as a neurotransmitter, facilitating the transfer of messages in the sections of the nervous system that control movement, coordination, concentration, memory, pleasure, and time perception. THC is thus able to disrupt certain mental and physical functions, causing the effect of intoxication.8

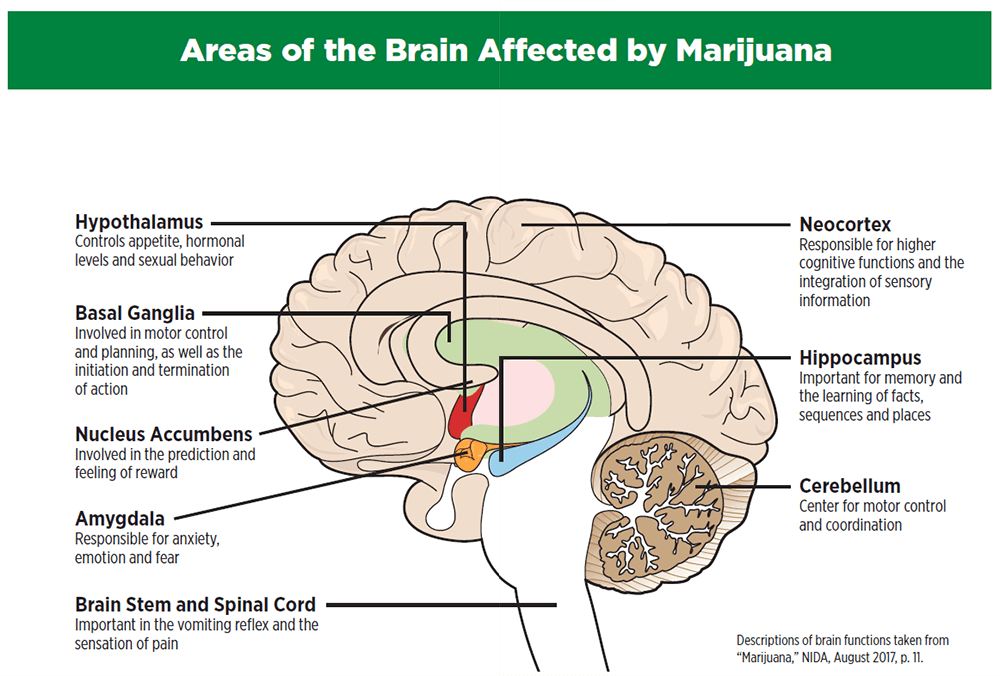

THC impacts the area of the brain known as the hippocampus and a portion of the frontal cortex, both of which have profound influence in the development of new memories and enable the shifting of attention (see illustration on pages 18–19). A NIDA report states:

As a result, using marijuana causes impaired thinking and interferes with a person’s ability to learn and perform complicated tasks. THC also disrupts functioning of the cerebellum and basal ganglia, brain areas that regulate balance, posture, coordination, and reaction time. This is the reason people who have used marijuana may not be able to drive safely….9

In 2007, a careful study exposed rats to THC at different phases of their life: before birth, after birth, and prior to maturity. All three samples demonstrated significant problems with learning and memory function for the rest of their lives.10 Other related studies showed that the exposure to THC prior to maturity increased the likelihood that the individual would self-administer other drugs to acquire the same or greater effect.11

One of the more concerning factors that medical research is revealing is the decline in potential IQ among adolescent users of cannabis. Persistent marijuana use disorder was found to occur among individuals who used pot frequently starting in adolescence. Their average loss was six to eight IQ points as measured in mid-adulthood.12 The same report revealed that those who used marijuana early showed a decline in verbal ability (equivalent to four IQ points) and in general knowledge between preteen and early adulthood.13 This process is somewhat connected with memory impairment, which is a consequence of changes to the function of the hippocampus, a previously mentioned part of the brain governing memory formation.

Two years ago, the Ottawa Citizen reported on research from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA): “Teens who start smoking marijuana early and do so frequently risk lowering their IQ scores.” The article goes on to state:

“The growing body of evidence about the effects of cannabis use during adolescence is reason for concern,” said Amy Porath-Waller, the CCSA’s lead researcher on the issue. “… There is a need to take a pause and consider that this is the future of our country. We certainly want to prepare our youth so they can be productive members of society in terms of employment so there certainly is reason that Canada needs to be concerned about cannabis use among young people.” Equally concerning, she said, is the perception among many Canadian youth that cannabis is benign and has no effect on their ability to drive or their performance in school.14

Ironically, Canada’s government is pushing to legalize marijuana even as the nation’s official department of health, Health Canada, is giving dire warnings about its proven medical hazards—all supported by recent, credible medical research. Health Canada’s website lists a decline in physical coordination and reaction time, loss of attention span, and reduced decision-making ability. It cites a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that demonstrated a permanent decline in IQ among persistent users.15 Health Canada also documents the associated risk of cannabis users’ developing psychosis or schizophrenia.

Indeed, several studies have now been published that link marijuana to increased risk for psychiatric disorders, which include psychosis (schizophrenia), depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders that lead to substance abuse.16 Additional research discovered that cannabis users who carry a variant of a specific gene are at a seven times greater risk of developing psychosis than users without the variant.17

Marijuana’s effects can even impact an unborn child if the mother is a user. On its website, under “Health effects of cannabis,” Health Canada states:

The substances in cannabis are carried through the mother’s blood to her fetus during pregnancy. They are passed into the breast milk following birth. This can lead to health problems for the child. Cannabis use during pregnancy can lead to lower birth weight of the baby.18

This government site also points out that such use by pregnant mothers has been associated with long-term developmental impacts on the children, including decreases in memory function, attention span, and problem-solving skills, as well as hyperactivity and a higher risk that the child will engage in substance abuse in the future.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that obstetricians counsel women against using marijuana while trying to get pregnant, during pregnancy, and while they are breastfeeding.19 Research has shown that for pregnant women who use marijuana, the risk of stillbirth is 2.3 times greater.20

Lung and Heart Damage

The American Lung Association reports that even if one ignores the dangers of the hallucinogenic ingredient (tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC), smoking pot is still very damaging to lung health:

Smoke from marijuana combustion has been shown to contain many of the same toxins, irritants and carcinogens as tobacco smoke. Beyond just what’s in the smoke alone, marijuana is typically smoked differently than tobacco. Marijuana smokers tend to inhale more deeply and hold their breath longer than cigarette smokers, which leads to a greater exposure per breath to tar.… Research shows that smoking marijuana causes chronic bronchitis and marijuana smoke has been shown to injure the cell linings of the large airways, which could explain why smoking marijuana leads to symptoms such as chronic cough, phlegm production, wheeze and acute bronchitis. Smoking marijuana has also been linked to cases of air pockets in between both lungs and between the lungs and the chest wall, as well as large air bubbles in the lungs among young to middle-aged adults, mostly heavy smokers of marijuana.21

We can add to these facts that marijuana’s higher-burning temperature, combined with its smoking method, causes increased loss of cilia in the lungs, leading to increases in rates of life-threatening emphysema.22

Interestingly, for years the Canadian Cancer Society has lobbied against tobacco smoking, winning widespread public support—yet many of the same people who wisely oppose tobacco usage often seem unconcerned about findings that marijuana is many times more damaging to the human lung. In the Annals of the American Thoracic Society, Dr. Donald Tashkin reported:

Marijuana smoking is associated with large airway inflammation, increased airway resistance, and lung hyperinflation, and those who smoke marijuana regularly report more symptoms of chronic bronchitis than those who do not smoke. One study found that people who frequently smoke marijuana had more outpatient medical visits for respiratory problems than those who do not smoke.23

As the National Institute on Drug Abuse reported on the study results, “Marijuana smoke contains carcinogenic combustion products, including about 50 percent more benzoprene and 75 percent more benzanthracene (and more phenols, vinyl chlorides, nitrosamines, reactive oxygen species) than cigarette smoke.”24

In another study, immunologist Dr. K.P. Owen related another concern: “Smoking marijuana may also reduce the respiratory system’s immune response, increasing the likelihood of the person acquiring respiratory infections, including pneumonia.”25

Nor is the heart immune. Widely published physician and researcher Dr. Andrew Pipe and scientist Dr. Robert Reid, of the Ottawa Heart Institute’s Division of Prevention and Rehabilitation, have expressed serious concern over ongoing or increased use of cannabis in the general public. The online heart and cardiovascular research publication The Beat reported in June 2017 on their findings, published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2014) and the American Heart Journal (2013):

The authors found that marijuana use has been associated with vascular conditions that increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, although the mechanisms by which that happens aren’t clear.… [Dr. Reid] also noted that marijuana use could be problematic for people with an irregular heartbeat, or arrhythmia, because it activates the sympathetic nervous system.26

The article emphasized two consequences of marijuana use on the heart: Both heart rate and blood pressure increase, and the blood’s ability to carry oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body is reduced. It summarizes the cumulative cardiovascular burden by saying, “The result is strain on your heart and a reduced ability to handle increased demands.” Note the following details, especially:

Within a few minutes after inhaling marijuana smoke, a person’s heart rate speeds up, the breathing passages relax and become enlarged, and blood vessels in the eyes expand, making the eyes look bloodshot. The heart rate—normally 70 to 80 beats per minute—may increase by 20 to 50 beats per minute or may even double in some cases. Taking other drugs with marijuana can amplify this effect.27

Second-Hand Smoke

Clearly, the impact of marijuana on cardiovascular health is negative, and becomes even more damaging if a person is both a tobacco smoker and a user of marijuana in any form. There is even the issue of harm to others nearby who are affected by second-hand smoke. In 2016, the Journal of the American Heart Association published a study showing the effects of exposure to only one minute of second-hand marijuana smoke, showing it has as much impact on blood vessel function as tobacco smoke, but the marijuana effect lasts longer.28

Just as is the case with tobacco, many have expressed worry about the impact of second-hand smoke from cannabis users. Legalization proponents frequently dismiss concerns of second-hand smoke, but new research is indicating the concerns are valid. In 1998, at the Winter Olympics at Nagano, a Canadian snowboarder by the name of Ross Rebagliati won a gold medal in his particular discipline. Shortly thereafter, he was disqualified and lost his medal due to a drug test in which he tested positive for marijuana. Rebagliati protested and claimed he had not used the drug, but may have been around people who were using it, thus causing the positive test. The decision was eventually overturned, since cannabis wasn’t a banned substance, but the snowboarder continued to claim he had not smoked marijuana during the period of the Olympics. Still, a shadow of doubt was cast over this athlete.

On December 1, 2017 the Edmonton Journal reported on a new study from the Cummings School of Medicine at the University of Calgary. In a recent publication of the Canadian Medical Association, CMAJ Open, lead researcher Dr. Fiona Clement found that “THC is detectable in the body after as little as 15 minutes of exposure even if the person is not actively smoking it…. [A]nyone exposed to second-hand smoke in a poorly ventilated room—including a kitchen, basement, or living room with the windows closed—will test positive.” The study goes on to explain, “It can take between 24 and 48 hours for the THC to clear from the system and Clement said that could be particularly problematic for employees who work in jobs where there is a zero-tolerance drug policy.”29

The article goes on to warn that people inhaling such second-hand cannabis smoke have reported getting high, which can also mean they are legally impaired behind the wheel. Thus, there is yet another public hazard associated with legalized recreational cannabis.

Cancer Risk

While studies are not yet conclusive regarding any increased cancer risk to the lungs as a result of marijuana smoking, several studies have made a firm link between cannabis and an aggressive form of tumor.

The studies show a clear link between marijuana use in adolescence and increased risk for an aggressive form of testicular cancer (nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumor) that predominantly strikes young adult males. The early onset of testicular cancers compared to lung and most other cancers indicates that, whatever the nature of marijuana’s contribution, it may accumulate over just a few years of use.30, 31

Chapter 2

Is There Any Good Reason to Get High?

Proponents of the legalization of marijuana offer many arguments concerning supposed benefits to decriminalization of the drug. In the next two chapters, we will look at some of those arguments: What about the role of “medical marijuana”? Is it possible that legalizing the drug will reduce crime and drug use overall? If we ban marijuana, shouldn’t we ban alcohol? And, in the end, if the pot user is only harming himself, why should society care?

What About Medical Marijuana?

For most of the last century, marijuana was an illegal or restricted drug. This made it difficult to do research on any potential medical properties. Under pressure from the pro-marijuana lobby, a number of U.S. states and the government of Canada decriminalized marijuana for “medical” purposes and began to permit legal growing operations for medical distribution. In some jurisdictions, an individual may have a permit to grow a limited amount of cannabis if that person is licensed to consume it for a “medical” reason.

The medical profession has advised caution over what they call a premature application of marijuana for medical reasons. There are a number of key concerns raised by physicians when it comes to prescribing cannabis for a given complaint.

The lack of research identifying any condition that will positively respond to an ingredient in marijuana: There is very little peer-reviewed and reproducible research that specifically identifies a medical condition that can be beneficially treated with cannabis. Hearsay, anecdotes and personal opinions are difficult to translate into a medical prescription.

The lack of research and clinical trials to determine dosages: Much research still needs to be done to identify which of marijuana’s ingredients should be prescribed, and the correct dosage of that ingredient, based on the patient’s weight, age, sex and severity of condition.

The lack of research on marijuana’s interaction with other medications: Before medicines can be prescribed safely, doctors need access to information about potential drug interactions. Not knowing this could have serious—even fatal—consequences.

The consistency of concentration of the medicinal ingredient: Currently, marijuana growers are not subject to regulations that would result in purity standards or consistency of concentration of the “medicinal” ingredients. Samples can vary significantly in terms of active ingredients.

The American Medical Association, which—on medical grounds—has opposed the legalization of pot, stresses the need to conduct thorough research into the pharmacology of cannabis before governments begin supporting cannabis as a pharmaceutical. Other drugs are required to go through rigorous testing, and choosing to make an exception for pot by sidestepping essential tests or “cutting corners” is deemed irresponsible by scientists. Note the following clause from the American Medical Association’s policy:

Our AMA urges that marijuana’s status as a federal Schedule I controlled substance be reviewed with the goal of facilitating the conduct of clinical research and development of cannabinoid-based medicines, and alternate delivery methods. This should not be viewed as an endorsement of state-based medical cannabis programs, the legalization of marijuana, or that scientific evidence on the therapeutic use of cannabis meets the current standards for a prescription drug product.1

In a letter to Canada’s then Minister of Health, the Canadian Medical Association similarly stated that there “remains scant evidence regarding the effectiveness of the herbal form of marijuana….”2

This was followed up a few months later by the Canadian Medical Association when it then stated:

The CMA still believes there is insufficient scientific evidence available to support the use of marijuana for clinical purposes. It also believes there is insufficient evidence on clinical risks and benefits, including the proper dosage of marijuana to be used and on the potential interactions between this drug and other medications.3

Associations of physicians resist the implementation of so-called “medical marijuana,” as there is currently a lack of solid research to determine which of the non-hallucinogenic compounds in the marijuana plant are effective for clinical application. There are indications that cannabinol, an ingredient in marijuana, may have potential for treating specific ailments, such as seizures. There is, however, much research needed to understand dosages, side effects, and other information that is required for a doctor to prescribe ethically. For those who insist on the medical benefits of pot, physicians point out that some dosage-controlled, carefully measured medications already exist: dronabinol (Marinol®) and nabilone (Cesamet®). Physicians can already prescribe either of these medications, though each still needs more research.

So, why is there still such a cry for medical marijuana? These and other cannabinol-based medications do not create the “high” in the user, but do contribute in most cases to an improvement in a specific medical condition. Is it because these clinically-approved medications do not give a high that they are not in demand? One also wonders: If pot is legalized, how long will there be a demand for medical marijuana? Perhaps the “medical” aspect is more excuse than reality for the majority of users who claim a medical reason for using cannabis.

Will Legalization Reduce Crime and Overall Drug Use?

Many argue that legalizing pot will undermine a key source of income for organized crime. The position is put forward that legalizing marijuana would reduce the contact of users with the criminal element and hence lessen the likelihood of contact with more serious drugs.

While it is obvious that declaring marijuana possession no longer a crime would technically cause a drop in the crime rate, it does not follow that the illegal drug trade would be significantly harmed.

Even as enforcement of marijuana laws has relaxed and access to the drug from storefront operations has increased, the use of other drugs has not declined. Despite easier availability of pot and decreased risk of prosecution, the consumption of even more damaging drugs is increasing. Most empirical research shows that marijuana is a “gateway” drug to more serious drugs. Whether it is legal or not, organized crime will benefit from increasing marijuana use.

Dr. Robert DuPont, first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, makes the following observation in The New York Times: “[P]eople who use marijuana also consume more, not less, legal and illegal drugs than do people who do not use marijuana.” He goes on to say,

Legalizing marijuana will have lasting negative effects on future generations. The currently legal drugs, alcohol and tobacco, are two of the leading causes of preventable illness and death in the country. Establishing marijuana as a third legal drug will increase the national drug abuse problem, including expanding the opioid epidemic.4

In fact, in some states in the U.S., legalization has resulted in a 400 percent increase in marijuana-related visits to emergency rooms, as reported by Dr. G. S. Wang of the pediatrics department of the University of Colorado.5

Several studies done in the U.S. and Canada have shown that because legalization has happened or is impending, people believe that it is a signal from their governments that cannabis is a safe and benign substance. Meanwhile, users are frequently unaware that the potency level of marijuana—the concentration of the hallucinogenic ingredient THC (tetrahydrocannabinol)—is now up to five times higher than it was in the 1960s.6

In jurisdictions where legalization or decriminalization has occurred or is occurring, provision is often made to allow those who have been deemed in need of “medical marijuana” to grow a limited amount at home, enough for one user. Different rules apply in various locations, but in Canada an individual with a medical marijuana license is allowed to grow between four to ten plants, depending on his or her situation. Just how problematic these individually licensed “medical marijuana” growing permits can be was recently reported on by one of Canada’s national newspapers, The Globe and Mail. Generally a left-leaning paper, The Globe and Mail has been supportive of legalization of recreational cannabis. Yet even this formidable publication is expressing shock at the situation that has developed.

An investigation published on December 1, 2017 entitled “Personal grow-ops emerge as targets for organized crime” explains how organized crime is very quickly becoming a force in the medical marijuana business and is using loopholes in the law to create massive “personal grow-ops” using medical marijuana as a cover. Authors Molly Hayes and Greg McArthur write:

The proliferation of personal yet industrial-scale marijuana farms, licensed and shielded by health privacy laws, has created a shadow market in which individual patients are collectively churning out as much marijuana as some commercial producers—with none of the scrutiny.7

They go on to say that some of these operations are targets for abuse by organized crime, the very group that was supposedly going to be put out of business by legalization. There are up to 600 of these “supergrower” operations supposedly producing medical marijuana. By manipulating weak laws governing this aspect of growing cannabis, some of these farms are cultivating nearly 2,000 plants, far more than needed for “medical” application. On the surface, criminals appear occasionally to “rob” the produced marijuana, but as Detective J. Ross of the Toronto Police Service stated, “If we are to believe that [criminals] are not working together for the purpose of profiting… we are just being naive. These are [not] just individuals wanting to grow a bit of pot…. This is big business.”8

Medical marijuana is undoubtedly being used by a number of “patients” as a smoke screen for the production of pot for illegal sale. The authors go on to explain:

Health Canada says a person convicted of drug charges within the past 10 years should not be able to obtain a licence. But the department says it only requires that applicants “attest” to a clean record. When police conduct a raid at an overgrown operation, they can seize only the surplus plants, which means there have been cases when they have had to leave hundreds of technically legal plants behind—in the hands of the accused criminals.9

The criminal element considers legalization and the weak laws around medical marijuana to be a gift. They can now, in many cases, grow with impunity—with reduced risk of prosecution and with minimal penalties—while harvesting profits, knowing they can easily undercut the government-set price of cannabis. They can also anticipate greater profits with the knowledge that marijuana is a “gateway” drug that will inevitably boost their business down the road in other hallucinogens and narcotics.

If Marijuana Is a Problem, Why Do We Not Also Ban Alcohol?

Marijuana proponents commonly compare “their drug” with alcohol. What are the facts? It is true that currently, as far as available statistics indicate, alcohol contributes to higher death rates due to heart attacks, circulatory diseases, cancer, gastrointestinal problems, homicides, suicides, and motor-vehicle and other accidents compared to those statistics for non-drinkers. Marijuana is relatively new on the scene as far as collectable data, and clear connections to disease are still in the early stages of being studied. And the accident rate of marijuana users is difficult to calculate due to currently inadequate means of measuring cannabis intoxication.

The basic problem with comparing the harm of alcohol to that of marijuana is that the pro-marijuana lobby tends to compare the impact of a large amount of alcohol usage with that of a small consumption of marijuana. This, however, is contrived; it is a deceptive comparison. An overuse of alcohol is a bad thing: It is hard on the liver, brain, and many other organs of the body, while a small amount of alcohol has been shown to have beneficial effects.

Of course, too much alcohol is grossly debilitating. But a little alcohol, especially natural wine, can be quite helpful. It relaxes the body and aids in the digestion of food by stimulating the stomach’s digestive juices. It is oxidized in the liver into natural compounds and leaves the system. Because it is water-soluble, it is eliminated relatively quickly. The THC in marijuana, on the other hand, is fat-soluble and is stored in fat tissue more quickly than it is absorbed into the blood. Hence, one can remain “high” without being aware of it for up to 48 hours. It also leaves toxic residue in the liver.

Even the Bible, while severely condemning drunkenness, speaks of wine as a blessing, if used in a proper way:

“Behold, the days are coming” says the Lord, “when the plowman shall overtake the reaper, and the treader of grapes him who sows seed; the mountains shall drip with sweet wine, and all the hills shall flow with it” (Amos 9:13).

A young man was advised by the Apostle Paul, “No longer drink only water, but use a little wine for your stomach’s sake and your frequent infirmities” (1 Timothy 5:23).

The Mayo Clinic, while stressing the need for control, shows the benefits of moderate alcohol consumption to include reducing the risk of heart disease and ischemic stroke, as well as reducing the risk of diabetes.10

Again, while excessive alcohol consumption will start to do damage, a moderate amount may be beneficial, according to a multitude of studies. Marijuana use, on the other hand, even in smaller amounts and especially in those under 25, whose brains are still developing, can lead to brain impairment (reduced memory and attention span, lower IQ, and poorer reasoning), as has been shown earlier in this publication. This is in addition to the other known and serious impacts of cannabis, including depression, lung and heart damage, cancer risk, and, in heavier users, a decided increase in suicidal tendencies.

While the abuse of alcohol can indeed be a plague, moderate usage is known to be beneficial in many cases. Research shows this is not the case with THC in marijuana.

Chapter 3

Isn’t It Merely a Personal Choice?

Some might ask, “Isn’t this a personal decision? If I’m the only one I’m hurting, what should society care?” However, marijuana does not merely cause harm to the individual users. Its impact is felt by entire societies.

Every society, especially those operating in a modern economic context, needs a population that is well-educated and motivated to be productive. This requires a strong cohort of working-age people who are able to analyse and make decisions and work at the peak of their intellectual ability. In an age of intense global economic competition, no society can afford to have a large percentage of its youthful citizens debilitated, even temporarily. Yet a significant body of scientific research demonstrates that marijuana does indeed have a negative impact on memory, attentiveness, and motivation. There is also a potential negative impact on the brain’s ability to learn, an effect that, according to research, can last for days or weeks depending on the individual’s history with the drug.1

Research points to the reality that one who smokes marijuana daily may be functioning at a reduced intellectual level most of the time. One review of 48 studies demonstrated that marijuana is associated with reduced educational achievement and reduced probability of graduating.2

One of the most prominent social concerns in the Western world today is increasing rates of suicide among our youth. Three studies performed in New Zealand and Australia, each with large sample sizes, found that cannabis users had an elevated chance of developing a dependency on other drugs, showing again that marijuana is indeed a “gateway” drug to harder and more dangerous substances. The research also showed that these users had a higher risk of attempting suicide than non-users.3

There is also a clear link between cannabis use and low socio-economic attainment. Heavy use is linked to a higher probability of lower income, greater welfare dependence, underemployment, criminal behavior, and lower life satisfaction.4, 5

Note the findings of the National Institute on Drug Abuse:

That said, people report a perceived influence of their marijuana use on poor outcomes on a variety of life satisfaction and achievement measures. One study, for example, compared people involved with current and former long-term, heavy use of marijuana with a control group who reported smoking marijuana at least once in their lives but not more than 50 times. All participants had similar education and income backgrounds, but significant differences were found in their educational attainment: Fewer of those who engaged in heavy cannabis use completed college, and more had yearly household incomes of less than $30,000. When asked how marijuana affected their cognitive abilities, career achievements, social lives, and physical and mental health, the majority of those who used heavily reported that marijuana had negative effects in all these areas of their lives.6

If even ten percent of our youth find themselves in a condition where their intellectual potential is limited, the cost to society becomes immense over time, not to mention the strain it puts on an economic system when a large portion of its citizens are not contributing to the economy in the manner they otherwise would or could.

I once served as a central office administrator of one of Canada’s largest school districts. One of my tasks was to chair hearings to decide on recommendations for students to be expelled from a school or the district. Over the years, it was obvious that the vast majority of these cases involved drugs (often crystal meth, ecstasy, and crack), and in most cases the issue started with marijuana. The situations were often heartbreaking. Students of significant potential were reduced to conditions where they were no longer functional academically or in in terms of their general behavior. Their lives were forever changed and their families devastated. Such situations play out in towns and cities across our nations, unfortunately in increasing frequency. Whether legal or not, marijuana is a “gateway drug” to harder drugs—and a gateway to the sorrow and loss of personal potential that inevitably follow.

One of the other social issues that is being raised by industry and police forces is the safety of workers and the public in an environment where recreational cannabis is commonly used. Numerous officials in the U.S. and Canada have expressed concern about the lack of good detection tests for drivers impaired by cannabis. Maintaining the safety of our roadways is something that should concern us all. Industry leaders, as well, have expressed concern about the increased risk of harm when workers who operate cranes, trucks, or other heavy equipment are impaired by cannabis while on the job—harm they may bring to themselves or to others.

Some large companies have been demanding mandatory drug testing. This presents a problem, as THC will be present in the user’s system for up to several days after use, depending on the amount consumed. Unlike alcohol, which is a water-soluble compound and which is rather rapidly oxidized by the liver, THC is fat-soluble, with excess stored in fat tissue and released more gradually over time. The result is that the user remains under the influence of the drug, often without being aware of it, long after use. For this reason, workers who are users resist the call for mandatory drug testing, whereas companies, concerned about the safety of all workers and bearing legal liability for ensuring that safety, seek mandatory testing to try to reduce the hazards in the workplace. Such concerns are well-founded, as research has demonstrated:

Studies have… suggested specific links between marijuana use and adverse consequences in the workplace, such as increased risk for injury or accidents. One study among postal workers found that employees who tested positive for marijuana on a pre-employment urine drug test had 55 percent more industrial accidents, 85 percent more injuries, and 75 percent greater absenteeism compared with those who tested negative for marijuana use.7

Cold Statistics, Real-Life Tragedies

All of these studies reflect more than numbers and statistics—they represent heartbreaking consequences in the lives of those damaged by marijuana use.

Some time ago, I received a letter telling the tragic story of a life irreparably altered from birth by pot. A section of the letter reads as follows: “I was what you would call a third-generation marijuana smoker. I was born into it…. My first breath taken in this world wasn’t a lung full of fresh air, but weed smoke…. I could not learn reading, writing and arithmetic at an appropriate pace with others my age.”

The author of the letter indicated that marijuana drew him into a crowd that used “weed” and other drugs. While under the influence of pot, he began committing crimes, as the drug reduces one’s sense of consequence. By the age of 21, he found himself on death row in an Arkansas prison, convicted of multiple murders committed under the influence of the “harmless” drug marijuana.

The writer, Kenneth Williams, came to terms with his situation and sought to warn others who had been, or might be, deceived by the lie that marijuana is harmless. While no one would claim that marijuana will lead every user to death row, Mr. Williams was determined to help others consider the role pot played in his life.

He took full responsibility for his crimes, though his life and learning ability were damaged even before his birth. He wrote a book to serve as a warning on this matter: The Unrelenting Burdens of Gang Bangers. In it, he wrote, “I share my story to warn others walking into darkness. Drugs like marijuana have led many to their deaths or a cold prison cell. It is harmful to users and to the nation. I am a living witness—at least for the time being.” Mr. Williams’ story bears out warnings provided by the Canadian Medical Association and, as we’ve seen, even by the Government of Canada’s own website. He was executed on April 28, 2017.

Chapter 4

A Deeper Reason for Life!

Perhaps we can begin to conclude with a few statements from an editorial in a recent Canadian Medical Association Journal by Dr. Diane Kelsall. The author is writing in response to Bill C-45, which was designed to legalize marijuana in Canada on July 1, 2018. Dr. Kelsall writes:

Simply put, cannabis should not be used by young people. It is toxic to their cortical neuronal networks, with both functional and structural changes seen in the brains of youth who use cannabis regularly. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health has stated unequivocally that “cannabis is not a benign substance and its health harms increase with intensity of use.”

Although adults are also susceptible to the harmful effects of cannabis, the developing brain is especially sensitive. The Canadian Paediatric Society cautions that marijuana use in youth is strongly linked to “cannabis dependence and other substance use disorders; the initiation and maintenance of tobacco smoking; an increased presence of mental illness, including depression, anxiety and psychosis; impaired neurological development and cognitive decline; and diminished school performance and lifetime achievement.”… The lifetime risk of dependence on marijuana is about 9%; however, this increases to almost 17% in those who start using as teenagers.…

Most of us know a young person whose life was derailed because of marijuana use. Bill C-45 is unlikely to prevent such tragedies from occurring—and, conversely, may make them more frequent.…

The government appears to be hastening to deliver on a campaign promise without being careful enough about the health impacts of policy.… If Parliament truly cares about the public health and safety of Canadians, especially our youth, this bill will not pass.1

Political leaders ought to be driven by a sense of what is good for their citizens, yet those who pander to groups who only want hedonistic pleasure—or who possibly have entrepreneurial interests eventually involving convenience store shelves and glamorous packaging—may be more interested in their own welfare than that of the nation.

The use of pot has been illegal in North America, and in many other countries, for good reason: It is, as science clearly shows, harmful to its users and to entire nations. Marijuana and other drugs like it rob the individual of potential and leave behind broken dreams and shattered lives. The loss of human potential to marijuana and other mind-altering substances is enormous.

Seeing Through the Smoke!

Why is it that, even though Western nations live in a time of extravagant wealth compared to any other period in the historical record, so many in our population today—especially the young—seek what is, essentially, an escape from reality in mind-altering drugs? Heated and air-conditioned homes, a multitude of gadgets, cell phones, and other amenities—luxuries abound in our lives. Food is generally plentiful, and most people’s basic needs are being met, yet many run after hallucinogenic drugs.

Obviously, all is not right. Something is missing. When our day-to-day lives are not fulfilling, we are not finding pleasure in our work and our relationships with family and friends, and we seek temporary pleasure through intoxication via substances that bring all kinds of potential harm, perhaps it is time to examine our lives more closely. An old saying claims, “There is a cause for every effect.” There is a cause for sadness, loneliness, and depression, and there is a cause for satisfaction and contentment. In most cases, our situation is a result of choices we have made. We have the ability to choose a way of life that provides happier lives for us and for our families, and thus we can avoid choices that create trouble and unpleasant realities—from which people then wish to escape.

Long ago, in a letter written to a young minister, a highly regarded citizen of Rome, a man of great education who had held high position and had been sought after by rulers of his day, gave the following advice as to how a person, young or old, can achieve a productive and satisfying life. The man, known today simply as Paul, wrote to a young Greek colleague named Titus:

Likewise, exhort the young men to be sober-minded, in all things showing yourself to be a pattern of good works; in doctrine showing integrity, reverence, incorruptibility, sound speech that cannot be condemned, that one who is an opponent may be ashamed, having nothing evil to say of you (Titus 2:6–8).

This description is the very opposite of being high, stoned, drunk, or in any other condition in which we are not in control of our minds. One of the characteristics critical for happiness and success is self-control. The inspired book of wisdom known as the Bible also stresses the need for us to be in control of our minds at all times: “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control. Against such there is no law” (Galatians 5:22–23).

Self-control cannot be exercised when one is drunk or high on a mind-altering substance. In that state, one is at risk of actions and words that can be regretted for a lifetime. The possible addictions that result can destroy families, careers, reputations, and potential. A sober mind is an invaluable defense against such calamities.

We are entering a difficult and dangerous period in the lives of our nations—nations that have for the most part utterly rejected formerly revered teachings on right and proper behavior, ethics, and morality. The concept that mankind is the creation of a God who gave instructions that were preserved through His sacred text is no longer widely accepted in the Western world, and the moral guidelines that directed behavior are no longer considered valid. At the same time, without such a set of moral directives, social order has started to unravel.

In November 2002, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Tony Blair, wrote an article that was published in The Guardian titled “My Vision for Britain.” In the article, Mr. Blair admitted that the moral dimension that had held society together and provided a sense of duty and responsibility was eroding. He wrote:

By the mid-1990s crime was rising, there was escalating family breakdown and drug abuse, and social inequalities had widened. Many neighbourhoods became marked by vandalism, violent crime, and the loss of civility. The basic recognition of the mutuality of duty and reciprocity of respect on which civil society depends appeared lost. It evoked the sense that the moral fabric of community was unravelling.2

Mr. Blair went on to suggest that the UK needed to create a set of guiding principles of morality, given that society no longer accepted the biblical values that had been its glue for the previous millennium. In that condition, a society gradually becomes visionless, with no future hope beyond this short human existence. To those lacking purpose, life begins to seem futile and meaningful hope evaporates. It is in such a state that a person sees no problem with reaching for escape from what seems a pointless reality.

As much as people would like to convince themselves that God is simply a part of an antiquated worldview, the evidence of the reality of a Creator is ever-present in the creation itself. Since the laws of probability demonstrate that this world cannot have come into existence by chance, a Creator must exist—and that Creator was not so callous as to leave His creation without guidance. His revelation provides real hope, which will supersede the desire to run from our challenges through using hallucinogenic drugs. For a better and more thorough understanding of why people try to escape from the present through mind-altering substances, visit our website TomorrowsWorld.org and search for our article “Why We Get High,” by Dr. Douglas Winnail. It is a most revealing study, one which you will find of great value personally and which can help you understand others who are struggling with substance abuse.

Knowing the full purpose for the creation—and for our lives—will enable us to cope with the disaster that unbridled social change, if not curtailed, will soon bring upon our lands. Understanding reality and living soberly in accordance with God’s direction will be a source of protection in the coming days. Note the words of Jesus Christ in this regard:

But take heed to yourselves, lest your hearts be weighed down with carousing, drunkenness, and cares of this life, and that Day come on you unexpectedly. For it will come as a snare on all those who dwell on the face of the whole earth. Watch therefore, and pray always that you may be counted worthy to escape all these things that will come to pass, and to stand before the Son of Man (Luke 21:34–36).

It is a tragedy when people, young or old, view “getting high” as a pleasure worth sacrificing so much for. Clearly, they do not see a purpose for human existence—a purpose that can be known and achieved. Our human mind is a treasure, brilliantly designed by a great Creator—one who plans to offer mankind an awesome future with potential undreamed of in the human sphere. To learn more, request our free booklet What Is the Meaning of Life? No chemical known to humanity can begin to deliver the wonderful sense of fulfillment God makes available to those who learn to take pleasure in living His way.

Endnotes

Chapter 1: If It’s Legal, Isn’t It Safe?

1 Christopher Bergland, “Does Long-Term Cannabis Use Stifle Motivation?,” Psychology Today, July 2, 2013, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-athletes-way/201307/does-lon....

2 “Marijuana and Youth,” Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, http://www.ccdus.ca/Eng/topics/Marijuana/Marijuana-and-Youth/Pages/defau....

3 H. Carliner, P. M. Mauro, Q. L. Brown, et al., “The widening gender gap in marijuana use prevalence in the U.S. during a period of economic change, 2002-2014,” Drug Alcohol Dependence 170 (January 2016):51–58, https://doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.042.

4 Marijuana, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), February 12, 2018, 8.

5 Vabren Watts, “Research Review Prompts NIDA Warning About Marijuana Use,” Psychiatric News, July 3, 2014, https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.pn.2014.7a8.

6 Kelly Grant, “What Canada’s doctors are concerned about with marijuana legalization,” The Globe and Mail, April 13, 2017.

7 J. C. Anthony, “The epidemiology of cannabis dependence,” in Cannabis Dependence: Its Nature, Consequences and Treatment, ed. R. A. Roffman, R. S. Stephens (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 58–105.

8 Marijuana, NIDA, 9.

9 Marijuana, NIDA, 10.

10 P. Campolongo, V. Trezza, T. Cassano, et al., “Perinatal exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol causes enduring cognitive deficits associated with alteration of cortical gene expression and neurotransmission in rats,” Addiction Biology 12, no. 3–4 (September 2007): 485–495. https://doi:10.1111/j.1369–1600.2007.00074.x.

11 T. Rubino, N. Realini, D. Braida, et al., “Changes in hippocampal morphology and neuroplasticity induced by adolescent THC treatment are associated with cognitive impairment in adulthood,” Hippocampus 19, no. 8 (August 2009): 763–772, https://doi:10.1002/hipo.20554.

12 Marijuana, NIDA, 17.

13 Marijuana, NIDA, 17.

14 Elizabeth Payne, “Early marijuana use can lower teens’ IQs, research shows,” Ottawa Citizen, April 20, 2015, http://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/early-marijuana-use-can-lower-t....

15 Madeline H. Meier, Avshalom Caspi, Antony Ambler, et al., “Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, no. 40 (October 2, 2012): E2657–E2664, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1206820109.

16 Marijuana, NIDA, 24.

17 M. Di Forti, C. Iyegbe, H. Sallis, et al., “Confirmation that the AKT1 (rs2494732) genotype influences the risk of psychosis in cannabis users,” Biological Psychiatry 72, no. 10 (November 15, 2012): 811–816, https://doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.020.

18 “Health effects of cannabis,” Health Canada, Government of Canada, accessed April 23, 2018, https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabi....

19 “Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation,” American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, published July 2015, accessed October 12, 2016, http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Commit....

20 Marijuana, NIDA, 37.

21 “Marijuana and Lung Health,” American Lung Association, last modified March 23, 2015, http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/smoking-facts/marijuana-and-lung-health....

22 M. L. Howden, M. T. Naughton, “Pulmonary Effects of Marijuana Inhalation,” Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 5, no. 1 (February 2011): 87–92.

23 Donald P. Tashkin, “Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung,” Annals of the American Thoracic Society 10, no. 3 (June 2013): 239–247, https://doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201212-127FR.

24 Marijuana, NIDA, 29.

25 Marijuana, NIDA, 25.

26 “Legalized Marijuana and Your Heart,” The Beat, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, published June 2017, https://www.ottawaheart.ca/the-beat/2017/06/27/legalized-marijuana-and-y....

27 Marijuana, NIDA, 31.

28 Xiaoyin Wang, Ronak Derakhshandeh, Jiangtao Liu, et al., “One Minute of Marijuana Secondhand Smoke Exposure Substantially Impairs Vascular Endothelial Function,” Journal of the American Heart Association 5, no. 8 (August 2016), https://doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003858.

29 “Second-hand marijuana smoke can cause bystanders to fail drug test: study,” Edmonton Journal, December 1, 2017.

30 John Charles A. Lacson, Joshua D. Carroll, Ellenie Tuazon, et al., “Population-based case-control study of recreational drug use and testis cancer risk confirms an association between marijuana use and nonseminoma risk,” Cancer 118, no. 21 (November 1, 2012): 5374–5383, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27554.

31 Janet R. Daling, David R. Doody, Xiaofei Sun, et al., “Association of marijuana use and the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors,” Cancer 115, no. 6 (March 15, 2009): 1215–1223, https://doi:10.1002/cncr.24159.

Chapter 2: Is There Any Good Reason to Get High?

1 “Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research H-95.952,” American Medical Association, last modified 2017, accessed April 23, 2018, https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/medical%20marijuan....

2 “Letter to Minister Aglukkaq,” Canadian Medical Association, dated February 28, 2013, https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/Letter-Agl....

3 “New ‘Marijuana for Medical Purposes Regulations’: What do Doctors Need to Know?,” Canadian Medical Association, accessed July 12, 2017, www.cma.ca/En/Pages/medical-marijuana.aspx.

4 Robert L. DuPont, “Marijuana Has Proven to Be a Gateway Drug,” The New York Times, last updated April 26, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2016/04/26/is-marijuana-a-gateway-....

5 “Marijuana-related ER visits among kids quadruples at Colorado hospital: Study,” Toronto Sun, last updated May 8, 2017, http://torontosun.com/2017/05/08/marijuana-related-er-visits-among-kids-....

6 Marijuana, NIDA, 15.

7 Molly Hayes and Greg McArthur, “Personal grow-ops emerge as targets for organized crime,” The Globe and Mail, December 1, 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/investigations/marijuana-grow-ops-g...

8 Hayes and McArthur, “Personal grow-ops”

9 Hayes and McArthur, “Personal grow-ops”

10 Mayo Clinic Staff, “Nutrition and healthy eating,” Mayo Clinic, August 30, 2016, https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eatin....

Chapter 3: Isn’t It Merely a Personal Choice?

1 Susan F. Tapert, Alecia D. Schweinsburg, Sandra A. Brown, “The Influence of Marijuana Use on Neurocognitive Functioning in Adolescents,” Current Drug Abuse Reviews 1, no. 1 (2008): 99–111, https://doi:10.2174/1874473710801010099.

2 John Macleod, Rachel Oakes, Alex Copello, et al., “Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies,” The Lancet 363, no. 9421 (May 15, 2004): 1579–1588, https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4.

3 Edmund Silins, L John Horwood, George C. Patton, et al., “Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis,” The Lancet Psychiatry 1, no. 4 (September 2014): 286–293, https://doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70307-4.

4 David M. Fergusson, Joseph M. Boden, “Cannabis use and later life outcomes,” Addiction 103, no. 6 (June 2008): 969–978, https://doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x.

5 Judith S. Brook, Jung Yeon Lee, Stephen J. Finch, et al., “Adult work commitment, financial stability, and social environment as related to trajectories of marijuana use beginning in adolescence,” Substance Abuse 34, no. 3 (July 2013): 298–305, https://doi:10.1080/08897077.2013.775092.

6 Marijuana, NIDA, 23.

7 Marijuana, NIDA, 23.

Chapter 4: A Deeper Reason for Life!

1 Diane Kelsall, “Cannabis legislation fails to protect Canada’s youth,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 189, no. 21 (May 29, 2017): E737-E738, https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170555.

2 Tony Blair, “My vision for Britain”, The Guardian, November 10, 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2002/nov/10/queensspeech2002.tonyblair